On September 15th, 2022, as I climbed a massive hill on the Camino Frances I felt a powerful presence accompanying me.

"Cristina, is that you?"

I turned to check if she caught up with me. Cristina walks faster than I do and would let me march ahead while she walked in silence as she often stopped to meditate during the first few hours each morning of our Camino.

It was not her, I could see her further back, looking out to the northeast across the valley as the dawn turned the gray terrain to soft browns and muted yellows.

We were hiking the French route of the Camino de Santiago, a popular pilgrimage in Spain spanning 800 kilometers from St. Jean Pied de Port in France to Santiago de Compostela in Spain.

The Camino, or The Way of Saint James, is considered a transformative journey, and millions of pilgrims have embarked on it over the course of more than a thousand years.

Along the way, pilgrims take in the natural beauty of Spain, the kindness of locals, and the camaraderie of fellow travelers. It's categorically a physical, mental, and spiritual journey all wrapped into one long walk. It challenges you but also rewards you with a sense of accomplishment, well-earned, fresh, new perspectives, and a deep connection with yourself, others, and the world around you.

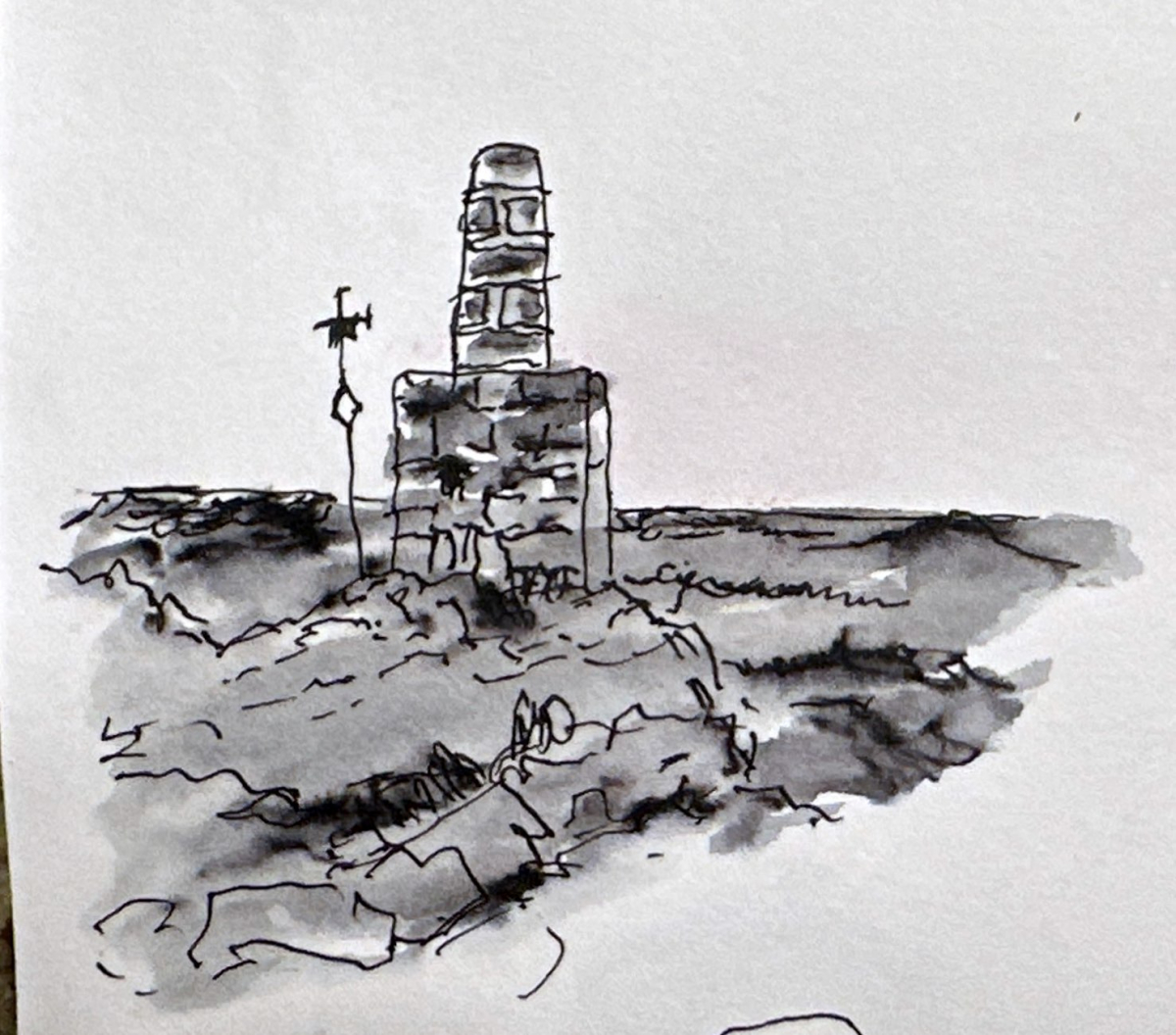

After a cursory Google search of this hill outside Castrojeriz, the only references I've been able to find for the Alto de Mostelares are comments in pilgrim's guidebooks and descriptions of the location in the blogs of pilgrims about their experiences on the Way.

Mostelares is the local name for a local peak not recognized or well-documented except by pilgrims. But, the hill is valued and well-regarded, in person, by millions. I am now one of those pilgrims.

This simple, barren hill holds significance for many pilgrims for one reason or another. I contemplated the sacred symbols and signs along the trail. I too consider this path sacred.

Across the top, we came upon a thoughtful shrine built as a memorial for a Spanish man named Manuel Picasso Lopez. It had a beautiful inscription. I took a picture to remember the kind words inscribed about how much his family and friends loved him.

"There are paths in this world that lead to heaven and this is the path of Manuel Picasso Lopez ..."

The shrine is adorned with all kinds of personal mementos - pictures of other pilgrims' loved ones, burden stones, prayer cards, and symbolic items whose true significance we may never fully grasp. I remember thinking these objects represent the faith, hope, and grief of thousands who have walked this hallowed path before me.

I placed a stone on the pile in remembrance of a friend's son who had taken his own life.

"Maybe, it's Eddie that's visiting me?" I wondered aloud.

I said a prayer, asking God to comfort his mother.

"Eddie, why are you visiting me? Go comfort your mother," I muttered, just as Cristina rounded the corner. I didn't want her to question the emotions bubbling up in my eyes and not be able to explain myself, so I turned and walked on before she arrived.

For the next few kilometers, spanning roughly two hours, I found myself moved by the evidence left by the creators and devotees of this awe-inspiring trail. This enchanting experience stirred something deep within me, the reason for which eluded me, so I simply allowed it to walk with me, step by step. Although I was physically alone, I felt a profound sense of companionship, my emotions running high, yet I felt at peace as I continued to walk, think, and immerse myself in the experience.

For me, this Alto de Mostelares bookmarks the first third of the Camino Frances. For me, this first third was like a preparatory and necessary unraveling of 59 years of life's illusions.

I often found myself humming a favorite Joni Mitchell song from the '70s.

"I've looked at life from both sides now, from give and take and still somehow, It's life's illusions I recall, I really don't know life at all."

As Cristina and I walked contemplatively deeper into the Meseta, with nothing but the bare essentials we needed in our backpacks, the Camino was providing all of the food, water, shelter and signage to always move us forward in the right direction, no guides required, only mindfulness to the signs left by others along the Way.

The Camino feels like it was intentionally designed by a higher power, whether it be God, a pagan deity, or one of my own imagined Stoic gods, created intentionally to dismantle my previously-held irrational beliefs and illusions about what truly matters in life.

Months later, I tried to describe the experience to my sister.

"It's as if you have this afghan knitted with one long strand of yarn. You tie one end of the strand to a tree as you depart St. Jean Pied de Port in France, and then walk, unraveling the afghan with each step. Somewhere about ten to fifteen days into your journey, once your afghan of illusions unravels, you are left with one long string of yarn you can yank loose from the tree and begin to mindfully knit back into a more practical, less illusory, and more meaningful view of life."

Living a life free of illusions is not easier. By definition, I believe it to be harder. I recognize now how the knitting-back-together of one's life perspective, its purpose, and meaning cannot happen overnight or even in a fortnight.

Veterans like to say the Camino is not about reaching the destination, but the journey. Your "real Camino," as they say, starts upon reaching Santiago. I agree. It's all a metaphor for life.

I continued into the second third of our Pilgrimage, contemplating the mystical and often introspective stage called La Meseta. I pondered all the lives represented in the hundreds, if not thousands of churches, cemeteries, shrines, and cairns we passed along our Way.

I meditated on the idea of millions of Pilgrims who, for over a thousand years, have walked The Way of St. James and the hundreds of thousands who were doing it along with us this year alone.

Looking back now, all of this reflection was setting me up for what happened next.

Let me suggest the Camino de Santiago is a transformative endeavor and can change how you think about time, distances, and what is important in your life. I believe that's why so many people make significant changes in their lives upon their return. I think it is why some embark on the journey in the first place when faced with challenges, such as divorce, losing a job, starting a new career, or mourning a loved one.

Modern technology allows us to talk, Facetime, Zoom, or Whatsapp and share all kinds of experiences as if we could be together, halfway around the world. But is it the same as being together for real? I cannot say.

Here, on the Camino, and for the first time in my life, I perceived the presence of someone else with me while I walked alone, and I did not understand why the thought made me emotional. I teared up. It gave me the chills. So much so that I turned back several times to see if someone trailed me or if it was Cristina. It was not. I walked alone. But I was not alone. I walked with someone and it felt like many.

Well, later in the day my sister called. After settling into our accommodations in Frómista, we had set about buying supplies for the next day's walk. While in a store, the call came in. I let it go to voicemail and read the transcription a few moments later.

She said, "Please call me asap, I don't think I can leave this as a voicemail."

I knew. I knew he had passed. At that moment, I realized it was my father that had accompanied me earlier. I knew.

I stepped out of the store and returned Lisa's call.

Not often do we get to plan a death. And if we do, we often deny ourselves the importance of contemplating its significance. It comes as an unexpected visitor—a shock. We spend our time living for and planning for life in an imagined future, anticipating the next time we will speak to each other again, not imagining enough how one day we will never speak again.

If we practiced more of these uncomfortable negative visualizations, we might find the strength to enjoy the right here and now. I suspect many of the deaths memorialized along the Way came as surprises that rocked the worlds of those left behind, like the death of my friend's son or my father's passing, albeit his was somewhat expected.

For sure, we all understood Dad could pass anytime. He was 86 years old and always said he was ready. Knowing this, I would call him on my cell phone and talk with him almost every day while on my training walks for over two years, preparing to walk the Camino.

And here we were in Spain, climbing this obscure hill, El Alto de Mostelares, on the way out of Castrojeriz when my father passed away, some 8500 kilometers away, in Warren, Oregon, USA, give or take a few kilometers, give or take an hour or two per the death certificate, not able to be with him.

We were executing a stage of our life plan including ticking off the box on our bucket list to walk the Way of St. James. I'm sure we would not have planned to walk the Camino if we had known it was his time. But we made a choice, and the time and distances involved will compound the consequences of this choice for me, forever.

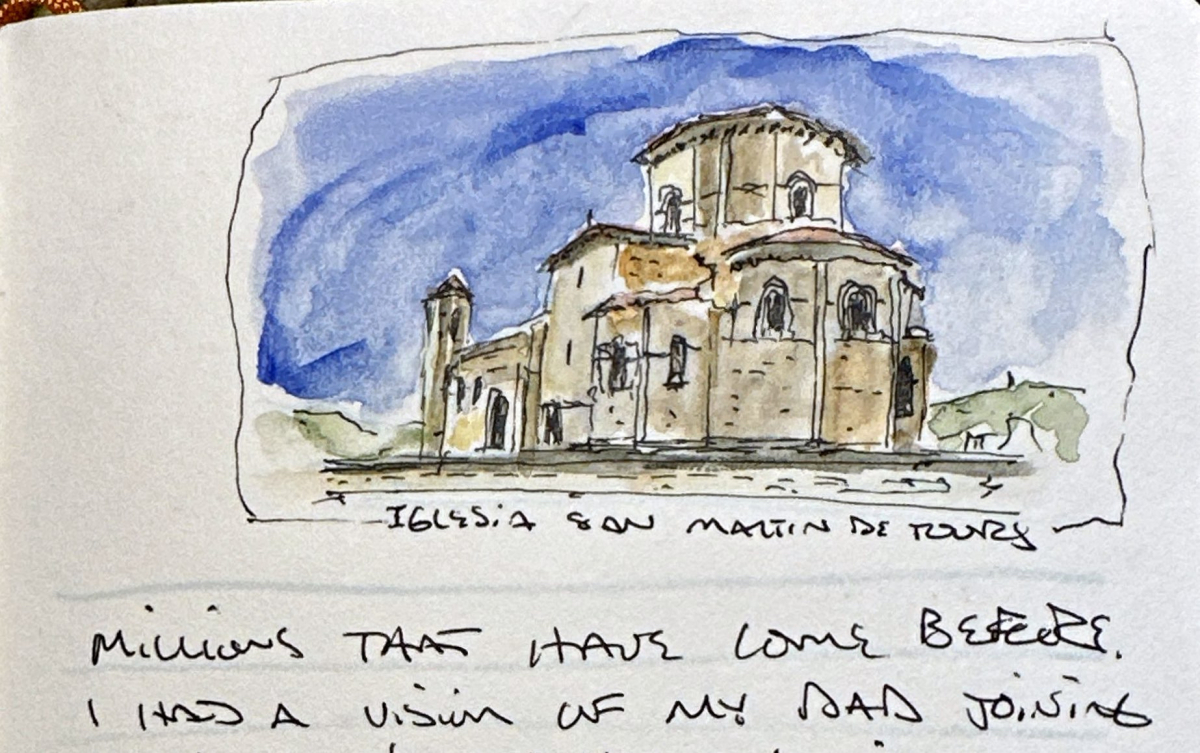

A few minutes after getting the news, we ran into Daniel, one of our Camino-family brothers sitting in front of the monastic church of San Martín de Tours. After hugging our greetings we sat down on the steps looking up at the beautiful Romanesque Church before us.

Cristina surprised me by immediately saying to Daniel, "Lance's father passed away today."

This image of the church is from my Sketchbook Journal.

After a few heavy sighs. Daniel asked, "What are you going to do? Go home for the funeral?"

"No, " I said, "I spent a lot of time talking with my father on the phone while out walking in preparation for the Camino. My dad told me how excited he was for us."

Daniel said, "Well, I guess this changes the meaning of your Camino."

It did.

From that day forward, as we continued toward Santiago, our 'Camino' took on a significance that I am still trying to comprehend.

For the next weeks, I walked many, many kilometers with my father. I crossed the Meseta with him, carrying him in my heart, keeping him on my mind.

Several times I grabbed for my phone to call him out of habit, out of reflex, which is something I will never be able to do again. I can never talk with my Dad again by phone.

We all have these stories of losing loved ones and how it changes us. I cannot say my story is unique.

As we walked on, I can say we grieved my father's death, but we also celebrated his life and both thoughts made me emotional.

I've been thinking lately about how this experience showed me there's a reciprocal and direct relationship between life and death, or death and life, if you prefer that order. It might depend on if you are a believer or not. It's ok if the order is important to you. It's not to me.

On the Camino I came to see life and death as two different but reciprocal sides of a coin. You cannot have one side without the other. After certain deaths comes a new life. That's likely an eternal truth of sorts. My life is now different since my father passed, if that is what you would call new.

This quote from Joseph Goldstein, 'Everything changes and becomes otherwise,' deeply resonates with me now. It encapsulates a profound understanding that nothing remains static, and transformation is an inherent part of life's journey. The question is how can we best embrace the inevitable?

I am at home now. It's been several months since completing our first Camino.

I'm walking almost daily the same 1.5-mile circular route from my doorstep and around our Bella community that I walked with regularity before our Camino.

I'm walking the same path I walked for two years in preparation for our Camino.

I'm walking the very same path I would pull out my iPhone and call my Dad, daily, all through COVID, and until the day we caught our plane for Spain.

I have reverence for our conversations, for our time well spent together. I sometimes walk and contemplate the stories he told me of his life and the lives of the people he loved. I think of the stories I told him and of the stories I could have told him about my life and the lives of the people I love. We both worked through many regrets on those phone calls. They were the conversations of two mature men who have each made errors but continued trying to make a better decision than the previous. I often wonder if our approach to life is genetic.

I understand now that I was walking a holy and most sacred path with my Father around my neighborhood and on our Camino. Here's why I think this.

I don't think it is the destination of the Camino de Santiago, a pilgrimage to honor the shrine where the remains of St. James are believed to be buried that makes the path a sacred one. It's not the destination, or those final precious steps into the Praza Obradoiro, ushered in by the sounds of bagpipes, or seeing that massive Cathedral in person that makes the Camino so incredible.

It's the energy each Pilgrim brings to the Camino and leaves along the Way, a footstep, a meaningful conversation, a kind act, laughter, a story, a "Buen Camino", a prayer, a burden represented by a stone left at a shrine, and the tears that make the Camino sacred. Yes, it is all that and more, but I think it is more about love.

Love is what makes things sacred. Love is what I carried walking up that obscure hill a kilometer or two outside of Castrojeriz. Love is what I received from my fellow Pilgrims, the hospitaleros (volunteer caretakers who provide accommodation and assistance to pilgrims along the Camino) and the local Spaniards who always wished me a "Buen Camino."

I wondered if they saw or intuited how important this walk had become for me. Perhaps that's why they treated me so kindly. But then again, that's just how people are on the Camino - kind, generous, and compassionate. And now that I'm back home, that's how I want to be too.

I love the stories my father would tell me by phone on our long daily walks together around my community.

I asked him once if he could go walk a Camino or Pilgrimage in Europe where would he go?

He said, "I would walk through the hills, vineyards, past the villas and cities of Tuscany."

If I could call him today, I would tell him of our Camino and how one day I now want to go walk through Tuscany. It's no small thing to inherit the dreams of your father. It's another to realize them.

For now, I search for and read any authentic story I can find about the Camino. I also love music and poems about the Camino. Here is one of my favorite Spanish poems. It's fitting for this writing.

“Caminante, son tus huellas

el camino y nada más;

Caminante, no hay camino,

se hace camino al andar.

Al andar se hace el camino,

y al volver la vista atrás

se ve la senda que nunca

se ha de volver a pisar.

Caminante, no hay camino

sino estelas en la mar.”

~Antonio Machado

Here's an English translation of the poem.

"Walker, your footprints

are the path and nothing more;

Walker, there is no path,

it is made by walking.

Walking makes the path,

and looking back

you see the trail that will never

be walked again.

Walker, there is no path

only wakes on the sea."

~Antonio Machado

My father always spoke of writing a novel. I always tried to encourage him. As far as I can tell he never finished. I regret I was not successful in getting him to write more. But everyone would say he was quite the story teller.

Here's my rewritten version of Antonio Machado's beautiful poem, that I dedicate to my father.

"Storyteller, your words

are the story and nothing more;

Storyteller, there is no story,

it is made by your telling.

Telling makes the story,

and looking back

I remember the stories you will never

tell again.

Storyteller, there is no story

only story-wakes on the sea."

Looking back on my Camino journey, I realize that it was not about completing a physical challenge or crossing off a bucket list item. It was about connecting with the world around me, experiencing love and loss, and finding a way to be in the moment, even the mundane everyday moments.

I learned, once again, that life is a journey, full of twists and turns, highs and lows, joy and sorrow. And like the Camino, it's not only about the destination, but the experiences we have along the way and the people we meet.

My father is no longer with us, but his spirit lives on in my memories and in the stories I tell. And as I continue my own Camino, I am reminded that we are all connected and that the love we share can transcend time and distance. If that's not an eternal truth, what is?

Let me say, "Buen Camino" to all who make sacred paths wherever they walk.

There's more story in my Camino, and I will write it as I am able.

In the meantime, rest in peace, Dad. Buen Camino.